See the original post on Medium here.

Special thanks to the many designers, investors, founders, and startup operators who spoke with me over the last few months about the space: Paul, Toby, Mark, James, Toi, Frances, Erhan, Alison, Jill, Matt, Yiliu, Darren, and others.

In this post, I’ll be discussing…

How the tech “hero narrative” has shifted from IT professionals to developers, and why designers are next

How the definition of a designer has evolved over time

Why the Figmas, Miros, and Zeplins of the world are just the tip of the opportunity iceberg

Key inflection points happening in the design tool space

What successful design tools of the future will look like

Democratization of Creation & Resulting Power Shifts

Ten years ago, TechRepublic published an article describing the advent of the decade of the developer, after years of tech progress being largely propelled by IT professionals. This may not seem prescient now given the market has grown into 26M software developers across the world, but back then this was not a crystal clear future. From a survey of CIOs in 2010 on developers vs. IT professionals, ~50% thought the IT market would shrink, while the other half predicted there was substantial room to grow.

“Today’s app environment is different. It’s faster. It’s more incremental. It’s multi-platform. It’s more device-agnostic. And it’s shifting more of the power in the tech industry away from those who deploy and support apps to those who build them. -Jason Hiner, “We’re entering the decade of the developer” (2010)

In recent years, we’ve seen the developer space rapidly grow in a variety of ways, from the $2B+ invested in open source software and dev tools in 2019, to the 8.9M+ mobile apps that exist in the world today. The space has largely trended towards notions of 1) democratization and 2) collaboration. While these two themes have paved the way for rapid technological advancement, they’ve simultaneously worked to commoditize development, not unlike patterns seen in the early 2000s, when momentum shifted from IT professionals to developers. In an attempt to increase speed and efficiency, more tools now target both developers and their non-technical counterparts, allowing new kinds of builders to take more ownership over the product development process. These tools have primarily taken the form of low/no-code applications, automating tedious hand coding in favor of sleek GUIs to configure applications. Development is increasingly becoming a utility — “anyone” can build now.

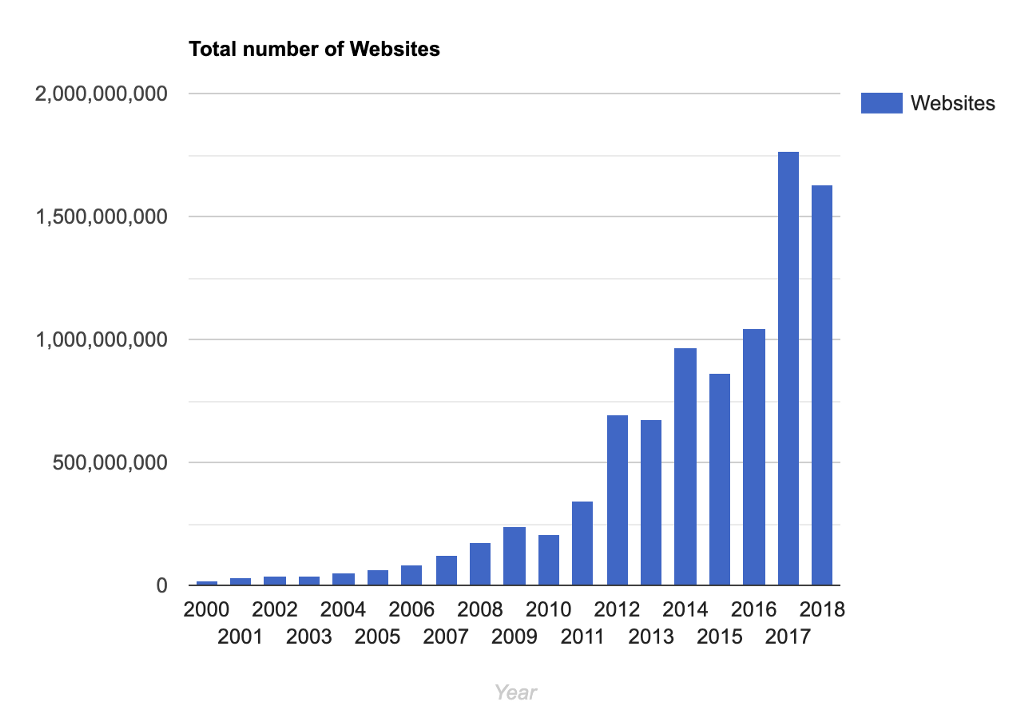

A prime example of this is website development. Gone are the days where you need to contract a web developer to build out your personal blog or company’s landing page. First came WordPress, then Wix and Squarespace. Now we are starting to see these tools evolve into more customizable, sleeker forms like Webflow and Bubble, which can output increasingly complex web apps. The difference between sites built on these platforms? Design.

With the democratization of these technical building blocks, we now have higher expectations around acceptable designs of a user interface and user experience (UI/UX). When we interact with software today, we expect a seamless product experience with great visuals and copy. In both consumer and enterprise (this is key!) use cases, there is less tolerance for boring, clunky tools. From a full-code to a low/no-code world, we’re ushering in the decade of designers.

“The interface no longer reflects the code; rather, the code reflects the design. We expect better, we deserve better, we demand better… it’s no longer optional to have good design.” — Peter Levine, on a16z’s 2020 investment in Figma.

A Brief Note on the Evolution of the Designer

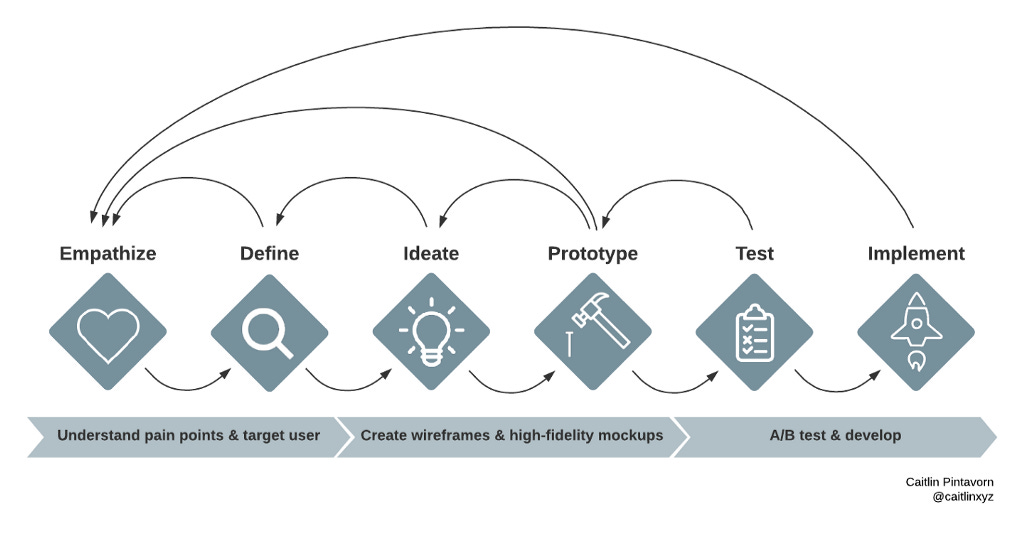

Over the years, design thinking as the workflow of choice for creating new products has persisted. However, the way in which a designer’s role existed along this process has changed. Historically, designers and developers worked as separate entities. A sample workflow in the early 2000s could have looked like the following:

Mac, a designer on a team, creates a website in Photoshop or Illustrator

He revises and iterates designs through extensive in-person team meetings

He then stores all file versions on-prem and in hard drives as a single source of truth

Mac redlines the exact design specifications manually before giving the full files and specs to Kenzie, the developer on his team

Today, the line between Mac, the designer, and Kenzie, the developer, has blurred. Designers are moving upstream, resulting in a new modern archetype: MacKenzie, the empowered designer. MacKenzie is designing in Figma, preferring a built-in, stateless, fileless management system for her mockups. Design specs are automatically marked up within Figma or through Zeplin. Increasingly, she’s coding parts of the designs herself or turning to no-code tools like Bravo Studio to get a working prototype.

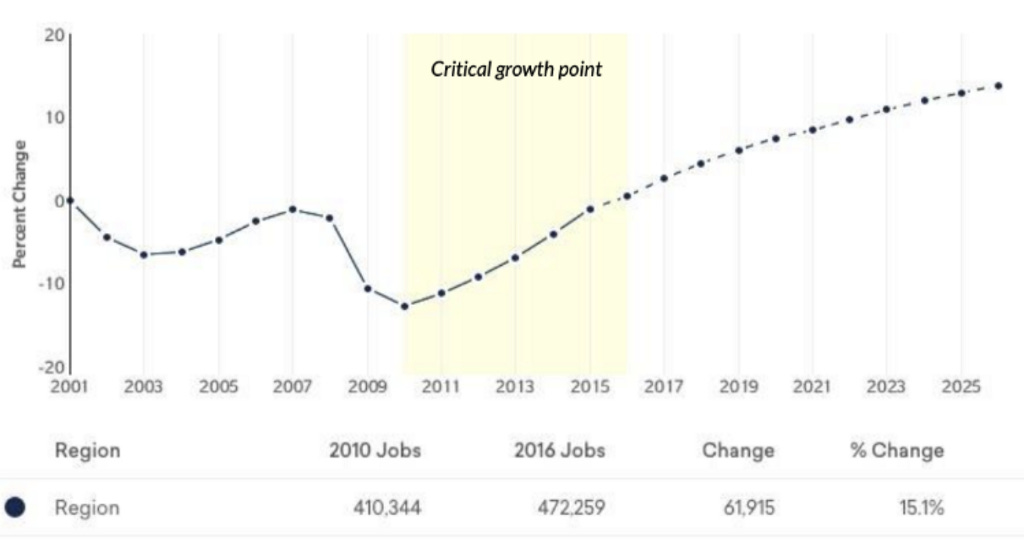

The job market has recognized this fundamental shift in the designer’s role and their ever-growing importance in the product-building process. There’s now around 1M UI/UX designers across the world as of 2019, with over 250K of them based in the U.S. across over 130K companies. And if we examine UI/UX designer job growth over the last 20 years, we can see a critical growth point between 2010–2016 — reflecting mass adoption of design tools as well as the increasing importance of design in product success outcomes.

The First Modern Design Wave

Along with the growth in UI/UX design jobs, we’ve seen an explosion in design tool usage, something I’ll be referring to as the first modern design wave (qualification: this is post-Adobe heyday). Figma, a collaborative interface design and prototyping tool, now boasts over 4M users, 700 3rd party plugins, and over 3M plugin installs. Miro, an online collaborative whiteboard platform, has over 8M users. And Zeplin, the single source of truth for design systems and style guides, has over 3M users. Though each have differentiating value-adds along the designer workflow, they share a few common characteristics: real-time collaboration and stateless/fileless version control systems. Their usage is also not constrained to designers. Any stakeholder, from developers to business strategists to senior executives, can access them and immediately get updated on a project’s progress.

Real-time collaboration and stateless version control are not novel concepts. But a key technical inflection point has occurred over the last decade that has enabled their adoption within design tools at scale. Specifically, we’ve seen a maturation of cloud services (faster software delivery, cheaper storage, etc.) that has enabled these design platforms to get rid of archaic hard-drive/on-prem based file management systems and to condense siloed communication workflows.

“First order inflection points signal a first wave of value creation, while aftershock [inflection points] are often what create multiple, larger cumulative value spikes. Sitting between these are Cambrian explosion events, which are rare in that they create singular points of value but are incredibly difficult to anticipate.” — Michael Dempsey, “On Inflection Points”

Borrowing language from Michael Dempsey’s recent essay “On Inflection Points,” these technical inflection points have been leveraged by the Figmas, Miros, and Zeplins of the world to transform the way designers work. These startups represent first order inflection point companies who have capitalized on the maturation of cloud services, and in turn, created additional market niches for startups to innovate. This is something we’ve started to see in the increased 3rd-party plugins built on top of these tools. And with COVID-19 as the Cambrian explosion event to top everything off, we now see a major push from design tools towards becoming collaboration-first and remote-friendly…as well as extra creativity from their users (e.g. Figma for workplace offsites, maps of Silicon Valley, etc.).

— @jsngr

With these companies as living proof of the market opportunity and COVID-19’s massive acceleration of remote-friendly tool adoption, it’s time for another instance of value creation in design. A second modern design wave is coming. And we’re seeing a glimpse of that future in the form of aftershock inflection points, where the opportunity will be for new kinds of design tools to dominate.

The Second Modern Design Wave

Aftershock Inflection Point #1: Online communities & open design have led to the democratization of design tools, further expanding the definition of a designer.

Designers and developers share a few key things in common: 1) they constantly publish their work online (personal portfolios, websites, etc.) and 2) they evangelize new tools to everyone around them. For designers, this is something we can directly see within online design communities. Informal communities have formed across existing social media platforms, like Facebook (HH Design), Reddit (r/Design), Slack (Figma Virtual Campus), and TikTok (UI/UX accounts), that serve to bring together designers interested in learning more about the industry, in getting critiqued on their own designs, and in getting inspiration for their next project. There are also more targeted platforms that have popped up, like Behance and Dribble, where designers showcase their work, create inspiration moodboards, and interact. This concentrated community-building has helped democratize design knowledge among hobbyists and professionals alike.

And for those looking to reduce their workloads (or just to not “redesign” the wheel), the concept of open design on these platforms is really interesting. We’ve seen how open source has helped make developers’ lives easier, and we’ve seen how huge companies can be built on top of this collaborative model. Now, these concepts are being applied to design. Figma Community, for example, has thousands of starter kits/templates that designers have made publicly available for others’ use (e.g. this iOS UI kit to help designs adhere to iPhone X layouts). And when someone posts about a project they’re working on Figma, they’re often asked to share the original file or design system used. All of these public resources have lowered the barrier of entry for aspiring and current designers, opening up access to quality templates and components for their next project.

Over the next few years, I expect the design tool space to continue moving towards open design and for startups to increasingly be built on top of this notion. Blush is a recent example of this. Launched a few months ago, it’s a customizable, modular tool that allows any kind of user to create new illustrations based off of an existing asset library that illustrators have been enlisted to contribute to (read this post from an illustrator on why she contributes to Blush).

Aftershock Inflection Point #2: Transition to remote and distributed workforces highlights the need for sync and async collaborative design tooling.

Whether design teams were already distributed or were forced into it by COVID-19, all workflows are happening virtually for now, and will likely continue to be the case for many companies well into mid-2021 (e.g. IDEO, Twitter). Right now, much of the collaboration happening within these teams looks the same: endless Zoom calls with shared screens of work progress. Remote AR/VR collaboration startups are challenging this norm by creating hyper-realistic working environments for teams to feel like they’re in one room. The Wild, for instance, allows teams to access a number of virtual spaces from any device (VR headset, laptop, phone, etc.) and collaborate (talk, draw, pull in library components, etc.) in real-time. I’ve seen The Wild in action, and it’s one of the most exciting glimpses into how AR/VR has progressed to provide fast, fluid experiences.

Aftershock Inflection Point #3: Design data is increasing, bringing about use cases for data-driven, automated design and tools for the computational designer.

With the shift to fully online workflows, the user interaction data captured within design tools is increasing, further highlighting use cases for data-driven, automated design. For instance, in every click on a prototyping tool, a designer is making needed adjustments (color, size, shape, position, etc.), applying critique feedback, and changing designs based on user research. Even after designing, they’re optimizing the finished products for development builds and monitoring any deviations. Startups that automate these workflows to some extent could help designers hone their creative processes.

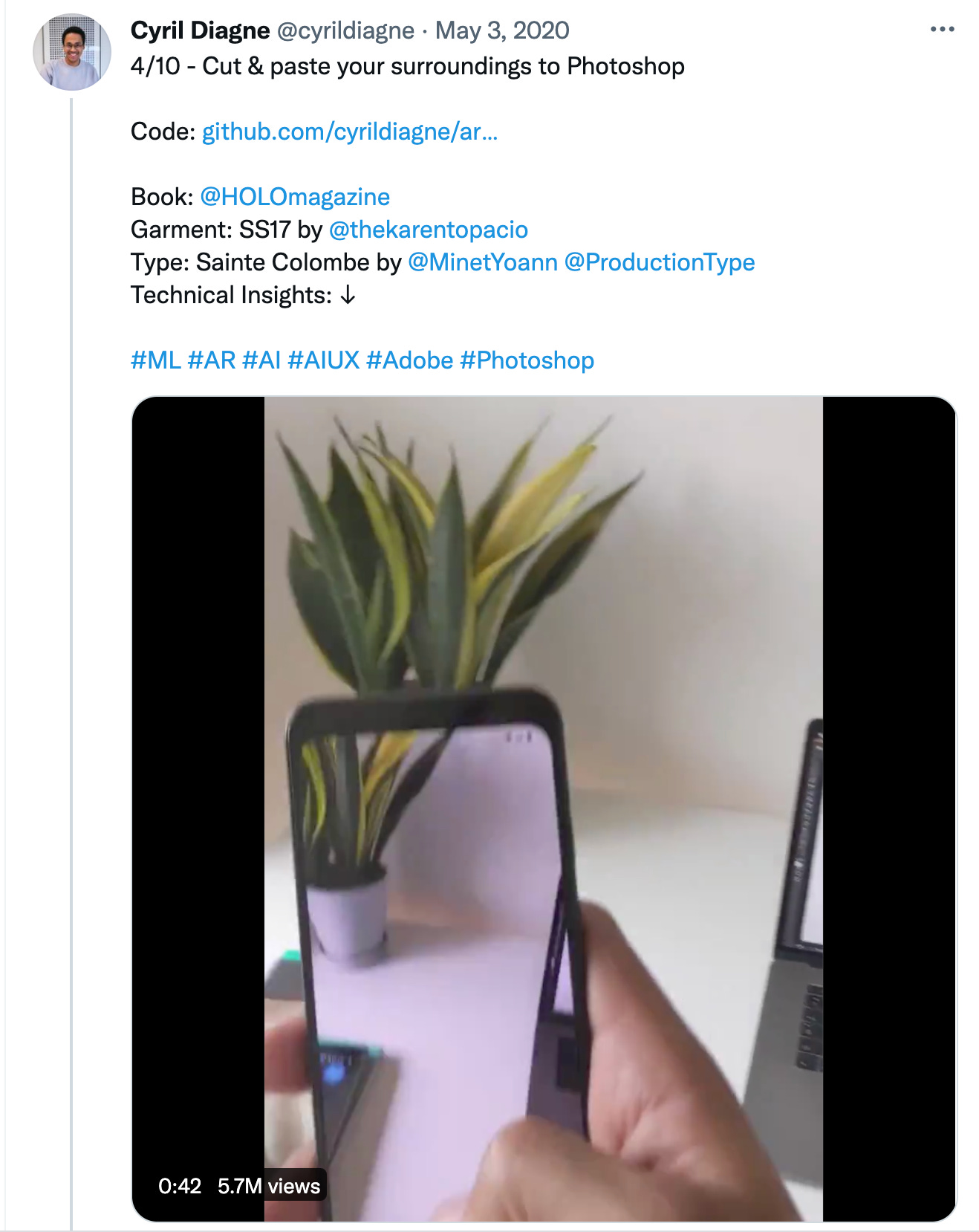

The flurry of AI/ML design plugins seen over the last few months are promising potential applications. One NLP example in particular (shown below) allows users to “talk” to Figma and direct it to output specific types of shapes vs. manually drawing it out. This also highlights potential for design tools to incorporate a vocal user interface (VUI) into their product. If these independent projects and startups like RunwayML are any indication, we’ll likely continue to see more AI/ML-based design tools.

— @jsngr

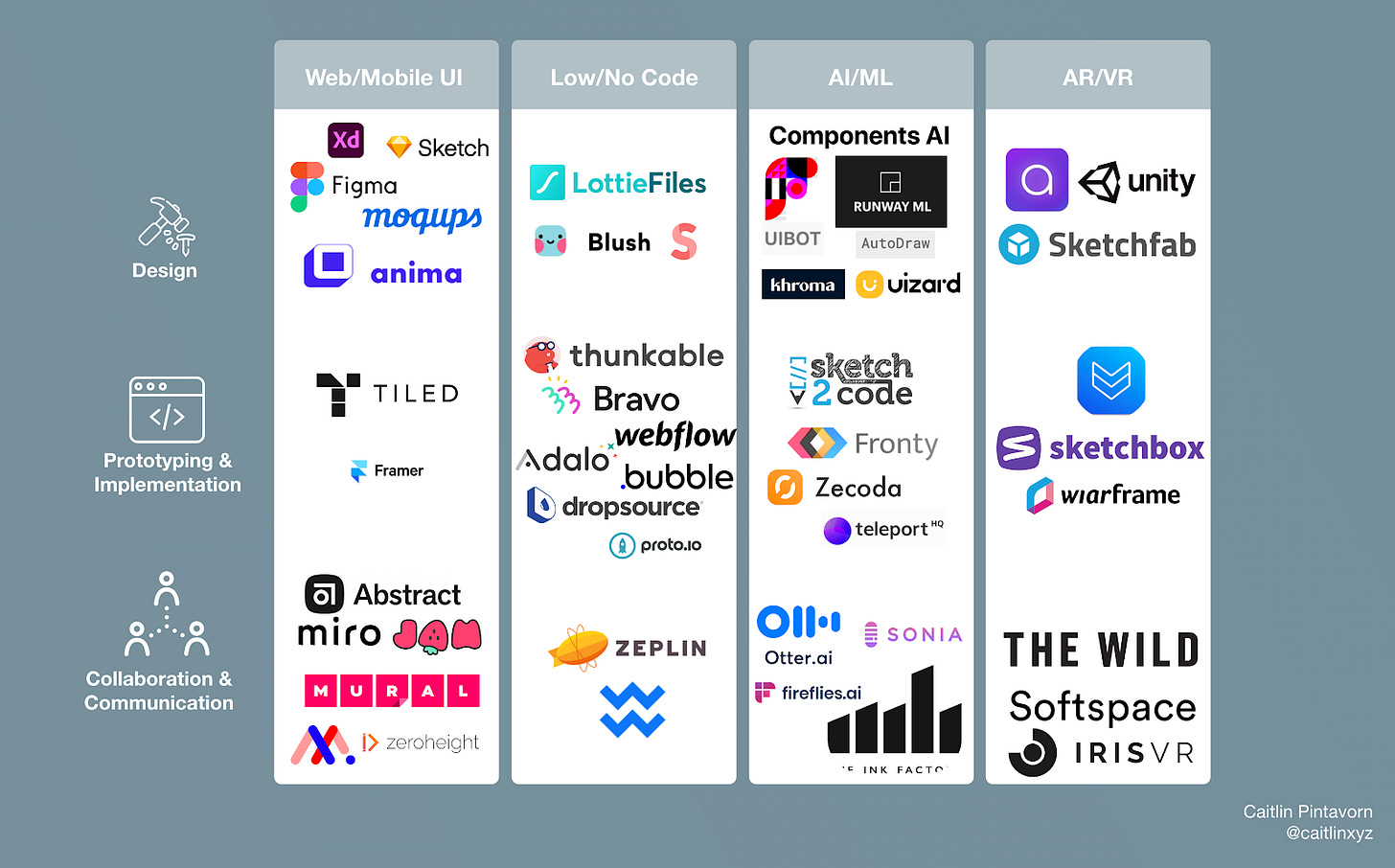

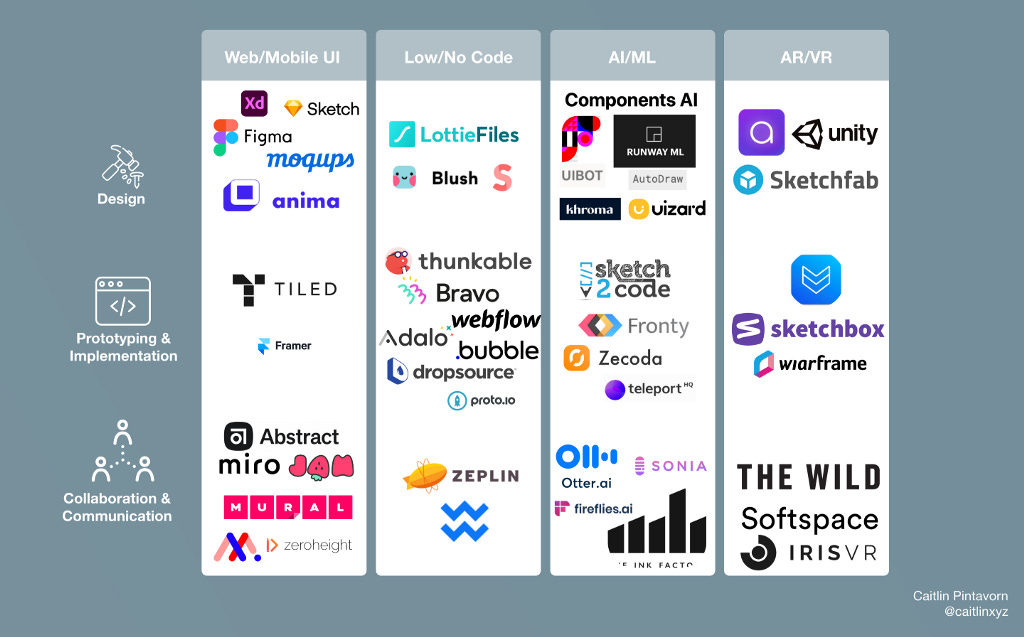

What I’ll be Looking for in the Design Tools of the Future

I view opportunities in the design tool space across the designer’s workflow, which has been condensed into 3 bulk categories on this market map: design, prototyping & implementation, and collaboration & communication. I’ve also categorized the startups within these portions of the workflow by their primary technological differentiator: traditional web/mobile UI, low/no code, AI/ML, and AR/VR. Some intersect across categories, but for the sake of simplicity, were placed in the ones I felt fit them best. When identifying and evaluating startups in the space over the next few years, there are a few things that will be important to look for, which I’ve narrowed down into 3 final takeaways:

Final Takeaway #1 — We should look for the tools optimizing for a bottom-up sales motion.

Whether it’s the latest landing page graphics or hottest tool, designers are major trend-adopters, building cult-like followings around their most recent obsession. Functioning like a ground swell, once there’s enough designer momentum, senior decision makers will often consider adopting the tool at the enterprise level (e.g. Adobe Creative Suite → Figma). After getting enough requests from existing employees or noticing a demand for working with the tool from potential hires, the senior decision makers at the firm will ultimately be the enterprise plan adopters. In order to get to this point a few factors need to make sense: 1) monetary switching costs, 2) marginal improvement in overall team efficiency, and 3) employee onboarding and training length.

Once a new design tool is actually taken up at the enterprise level, it becomes very sticky. For larger teams, it takes a significant investment (time, money, etc.) to transfer existing workflows onto the new tool and train employees to use it. Therefore, once they are embedded, tools stick around for at least 4–5 years until a better solution comes along and catches the designers’ eyes.

Collectively, designers serve as the gatekeepers for a successful B2B model. The most successful design tools of the future will recognize this and intensely focus on building up user love in online design communities, with robust individual user adoption and community buzz as likely indicators that successful enterprise sales motions will soon occur.

Final Takeaway #2 — The most successful next-gen design tools will be those that: a) integrate into & optimize current workflows, b) bundle & condense more parts of a workflow, or c) radically improve a part of a design process.

Retrospective pattern matching tells us design tools have historically added value in 1 of 3 ways: a) integrating into and optimizing current workflows (e.g. Zeplin as a single source of truth vs. Dropbox file management), b) bundling and condensing more parts of a workflow (e.g. Figma’s collaboration-first nature vs. XD’s lagging attempts), or c) radically improving part of the design process (e.g. Sketch as a dedicated UI/UX tool vs. scrappy Photoshop screens).

In the future, we can apply a similar categorical framework in predicting how successful new design tool startups will be at overtaking existing solutions.

Final Takeaway #3 — Whoever finds a way to leverage design data while preserving creative autonomy will dominate the next wave of design tools.

While the idea of improving designer workflows through data and AI/ML is exciting, it’s also important to keep in mind the highly creative nature of design. Designers will never allow for their creative process to become fully commoditized. But tools that are able to strike a balance between technology and autonomy will likely augment creative output, and become part of standard design repertoire. Two examples include RunwayML and Components AI. RunwayML has shown how we can empower designers to incorporate AI/ML in their design workflows without dictating their overall artistic direction. Within generative design, Components AI is a newer startup that was founded on the fundamental thesis that “the future of design tooling will be centered around a search interface, one that allows you to filter or define the constraints and quickly cycle through available outputs.” They’ve built a system where designers can set their work’s parameters from a seemingly infinite set of options.

If you’re working on something in this space, please feel free to reach out! I’d love to chat. You can email me at caitlinpintavorn@gmail.com or tweet me @caitlinxyz.

Designing the Future was originally published in The Startup on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.